Tianjin Updates

2025-12-12

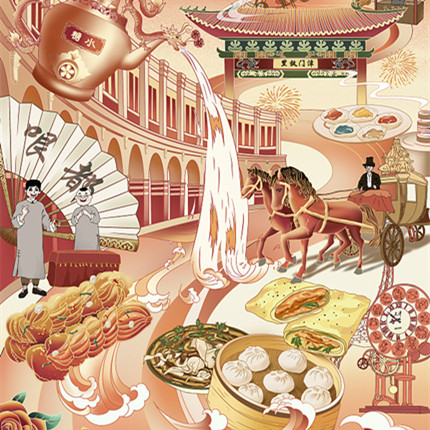

Salt of the earth

In the vast, sun-drenched coastal expanse of Tianjin's Binhai New Area in early autumn, the landscape shimmers. Here, where the waters of the Bohai Sea meet the land, lies the Tianjin Changlu Hangu Salt Field, a place that has been continuously harvesting salt for over a millennium.

read more- Lenovo factory in Tianjin goes carbon neutral

- Wuqing district drives forward with commercial hub development

- Brain-computer interface gives hope to paralyzed people

Copyright ©? Tianjin Municipal Government.

All rights reserved. Presented by China Daily.

京ICP備13028878號(hào)-35

Why Tianjin

Why Tianjin Investment Guide

Investment Guide Industry

Industry Industrial Parks

Industrial Parks

Health

Health Visas

Visas Education

Education Sports and recreation

Sports and recreation Adoption

Adoption Marriage

Marriage