How did ancient Chinese scholars travel to the capital for the imperial examination?

A new interactive installation at Gathering Talents around the Land — the Imperial Examination Culture of Ancient China, the renovated permanent exhibition of Beijing's Confucian Temple and Guozijian (the former imperial academy), provides the answer. Simply select the scholar's home province on a large screen and watch a vivid animation of his arduous trip to the capital — usually by boat and horseback — on a backdrop of a map, with the cost of the journey also laid out.

With about 130 exhibits alongside graphics and multimedia presentations, the exhibition takes visitors on a journey through the 1,300-year history of China's keju (the imperial examination system), which was designed to recruit civil officials for the bureaucracy, shining a spotlight on the system's profound impact on Chinese civilization and the world.

"With the fair selection of talent at its core, the imperial examination system broke the barriers of family status and created a channel for upward mobility for people from all social strata," says Li Xiaodi, an associate researcher at the museum.

"It ignited widespread enthusiasm for education among the public. This not only boosted the development of official and private schools and academies of classical learning, but also facilitated the inheritance and spread of traditional culture," she says.

Despite its eventual abolition in 1905 due to limitations such as rigid content, Li says, the system's spirit of objectivity and fairness still offers valuable insights for today. "Every mechanism must uphold fairness while combining flexibility and adaptability to the times, and it should be continuously refined through practice."

The imperial examination system was started in the Sui Dynasty (581-618), fully institutionalized in the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and ended in the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). Prior to this, the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC) employed a military meritocracy, while the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) adopted a recommendation system to select officials.

A major part of the exhibition showcases the whole process of how the system functioned during the Qing Dynasty via interactive experiences, installations and exhibits. Visitors will see original copies and replicas of paper relics, such as examination certificates that depict the facial features of candidates and answer sheets with neat handwriting.

A bronze sculpture of a Qing-era child immersed in his lessons brings to life the arduous childhood studies that laid the foundation for candidates' future imperial examination pursuits.

An exact replica of three examination cells is furnished with personal items like baskets and oil lamps. At night, candidates would dismantle the writing desk plank and lay it side by side with the seat plank in wall slots to assemble a makeshift bed. They were required to stay in their cell for a total of nine days and six nights and take three exam sessions, each lasting three days and two nights.

A short video projected inside a replica cell vividly shows a candidate answering questions, having simple meals, and finally curling up for sleep within the confined space.

After passing the xiangshi (the provincial exam) held in provincial capitals across the country, candidates had to scrape together enough money and travel long distances to take the huishi, or metropolitan exam, in the imperial capital (today's Beijing).

A Qing-era guidebook on display, named Tian Xia Lu Cheng (Routes of the Empire), details different water and land routes to reach Beijing, villages, towns, bridges, post-houses, travel distances and local specialties along the way, as well as how to guard against thieves.

The dianshi, or palace exam, the final stage of the system, was held in the Qing court and presided over by the emperor himself.

A scale model of the Hall of Supreme Harmony in the Forbidden City, along with miniature figurines, three-dimensional animation and background music, recreates a grand traditional ceremony. The emperor oversaw the solemn event, which was attended by all officials, as names of the jinshi — those who passed the ultimate exam — were announced.

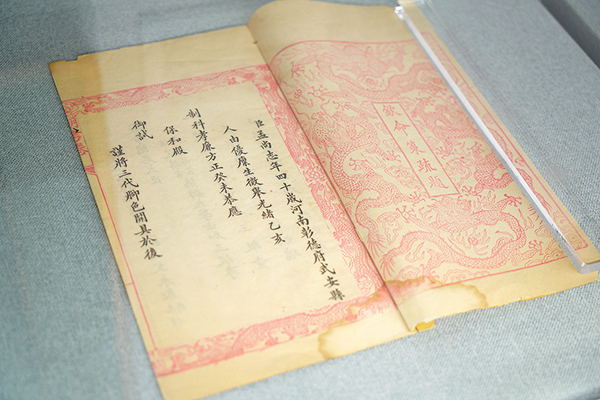

During the early Qing Dynasty, Examination Regulations by Imperial Command was enacted to regulate the imperial examination, including the selection of examiners, paper grading and anti-cheating measures. It was continuously revised and expanded thereafter.

Beyond recruiting civil officials, the imperial examination system also selected military officials. It assessed candidates not only on their archery skills, proficiency in weaponry and physical strength, but also their mastery of military strategy through a written test.

The exhibition also displays the tiny cheat notes secretly brought into the imperial examination sites, for example, palm-sized silk or paper slips covered in tiny, dense handwriting, and an ink box that was used to conceal the cheat sheet.

"The most common form of cheating was hiding reference materials in clothing or writing instruments. To counter such attempts, the authorities enforced strict security checks on both candidates and their belongings at the examination venues," Li says.

According to historical records, from the Tang Dynasty onwards, overseas scholars also came to study in China, taking the imperial examination and earning the jinshi title, thereby boosting cultural exchange.

While ancient Japan, the Korean Peninsula and Vietnam historically adopted China's imperial examination system to select officials, Western countries abstracted its core principle of fair competition through examinations to establish their own civil service systems, according to Li.

Sun Meng contributed to this story.