A tale of two fort frames

While each of the "trade paintings" has its own story, Kuang's favorite is a tale of two fort paintings — featuring a fort preserved in pigment, and another with a note that turns art into evidence.

About 20 years ago, while browsing an American antique shop in Washington, DC, Kuang encountered two paintings displayed as a pair: one of a bustling "country theater" and the other of a riverfront fort, which was a key part of Guangzhou's coastal defenses during the Opium Wars (1840-42 and 1856-60).

The dealer offered both paintings for sale — at a fixed price — no haggling. Kuang recognized the paintings as "sisters" and couldn't bear the thought of separating them.

"I knew their importance. I had studied China trade paintings, and I knew Haizhu Fort was famous," Kuang says.

While many depicted the famous fortification, this one uniquely displayed the two Chinese characters for its name, haizhu, on the front of the structure. That detail, Kuang says, "predetermined its irreplaceable historical value".

The painting offers a rare snapshot of Qing Dynasty coastal defenses, as Haizhu and other forts were critical in resisting foreign invasion, according to Kuang.

"The work witnessed — and in a sense lived through — a war that remains an enduring humiliation in Chinese history. The once-magnificent Haizhu Fort and the enormous Haizhu Rock no longer exist; what remains is only the crystallization of the painter's emotion," he says.

During the Second Opium War, Britain launched military action using the so-called Arrow Incident as a pretext. On Oct 25, 1856, British forces captured Haizhu Fort, seizing all 50 of its cannons, Kuang writes in his book China Trade — Qing Dynasty Guangdong Historical Paintings.

Kuang says many Guangzhou oil paintings of forts are labeled "The Dutch Folly", a label he considers unreliable as they often depict structures instead of the Haizhu Fort.

Years later, he found another painting he believed truly represented Haizhu.

Kuang spotted what he called "Haizhu II" on the website of a California antique gallery. He watched the price drop over time. He negotiated repeatedly, stretching the pursuit across five years, until the work finally fell into a range he was willing to pay.

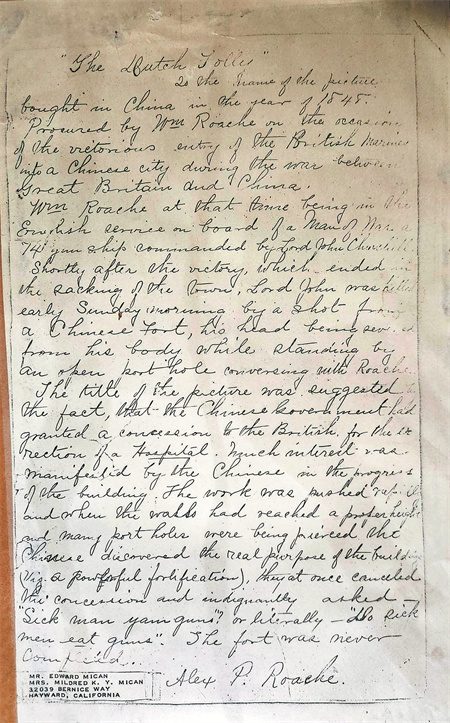

When the painting arrived, Kuang made an astonishing discovery. Affixed to the back was an old handwritten note, a detail the seller had never mentioned. The note stated that the painting, titled The Dutch Folly, had been purchased in China in 1845 by William Roache, who served aboard a 74-gun warship.

It is a piece of evidence preserved by the family of a British marine that reclaims a moment of fierce and effective Chinese resistance.

Written by a descendant of the original owner, the note provided a dramatic eyewitness account that remained unknown for at least one and half centuries: Lord John Churchill, the commander of the warship, was killed by fire from a Chinese fort while speaking with William Roache at an open gunport.

This account stands in stark contrast to the official British records, which, according to Kuang's research, claimed the commander died of a "long illness — brain edema" and was buried in Macao.

"Only after it arrived did I realize the note was even more important," says Kuang.

"When I saw the note, I felt the soldiers of that time deserved recognition and reward, because it might have been an important victory, but history left no record of it."

Kuang says he believes the British likely hid the truth to avoid damaging the morale of an expeditionary force already facing supply shortages far from home.

"When people talk about coastal defense, it's true that Qing forts and warships were technologically weak. But that does not mean they had no effect. If soldiers had today's defense conditions, many wouldn't have died. Yet, under those conditions, they still resisted invasion, and may have won certain battles," he says.

Such episodes likely occurred more than once, but reconstructing them requires painstaking comparison of naval logs, marine accounts, diplomatic correspondence and even missionary records, he says.

The note also explains that the painting's title, The Dutch Folly, was suggested by a story that reeks of mistrust or deception even today.

Chinese officials, it says, had initially granted the British a concession to build a hospital. As the walls rose and portholes were cut, the Chinese discovered the true intent behind the construction.

The officials realized the building was secretly being constructed as a powerful fortified position. "They at once canceled the concession and indignantly asked 'Sick man yami guns?' or literally — 'Do sick men eat guns?' The fort was never completed," Alex P. Roache, the buyer's descendant, wrote in the note.

For Kuang, uncovering the story behind the pair of fort paintings is an antidote to what he called the "second injury" of modern Chinese history — an emotional wound layered on top of the original defeat: the humiliation of sometimes having to understand one's own past through the eyes of the invaders.

In many online Opium War archives, some of the most widely circulated images are labeled "painted by British war artists", a curatorial reflex that quietly decides whose gaze defines the narrative, and underscores the need to protect and rediscover China's own oil-painting heritage.

"That was a huge shock to me," he says, describing the visceral pain of scrolling through archive after archive of dramatic scenes of "Chinese wooden ships being blown apart by British ships," only to find the works attributed, again and again, to the British side.

For him, the label isn't neutral; it was a warning about what gets lost.