A lost chapter of art

Kuang divides Qing oil painting into two broad streams. One consists of court paintings produced largely by Western missionaries and artists such as Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766), working under strict imperial supervision. The other comprises Guangdong export paintings made from the late 18th to late 19th centuries.

Far exceeding court art in scale and scope, these works captured the realities of Chinese life with a raw authenticity, creating a vital, if overlooked, chronicle of the era, he says.

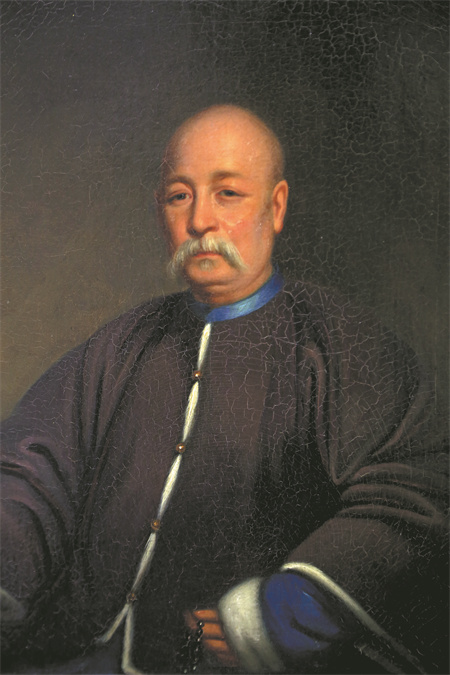

One example is the Portrait of Wu Guoying in Casual Attire, painted around 1800.

Wu founded the powerful Ewo (Yihe) Hong, one of the leading merchant firms in Guangzhou's Thirteen Hongs, the state-sanctioned cohort of trading houses that handled much of China's overseas commerce during the Qing era, especially from 1757 until the system collapsed in 1842.

When the portrait came up at auction in 2002, Kuang says he knew enough about trade paintings to recognize its exceptional quality.

The workmanship was "too good to be a minor piece", especially with its heavy zitan, or rosewood, frame, Kuang says.

The painting "vividly and accurately" depicts the subject's solemn expression, well-defined muscles, skeletal structure and facial features, giving the portrait an almost spiritual presence.

The artist skillfully rendered a three-dimensional spatial effect on a flat surface, making the figure appear lifelike, almost like a living sculpture, he says.

Kuang now argues that this portrait represents "the pinnacle of global oil painting achievements at the time", and "for the next 170 years, these works continued to lead China's oil-painting scene".

That conviction was reinforced when Gong Naichang, a student of the renowned Chinese artist and educator Xu Beihong (1895-1953), came to view the portrait.

According to Kuang, Gong's hands were shaking as he studied the canvas. He admitted that no one in his teachers' generation could have painted at such a level and that they knew almost nothing about this chapter of art history.

In the essay Endless Nostalgia — Oil Paintings of the Late Qing published in a magazine in April 2010, Kuang noted that in the late Qing, oil painting in China briefly surged to a scale never seen before or since.

Before that period, oil painting appeared only sporadically in Chinese records. Afterward, through the first half of the 20th century — despite waves of painters returning from overseas studies and training new students — truly outstanding works remained rare.

In terms of realistic depiction — and art as historical record — late-Qing oil painting was a visual archive, he wrote.

"So I am convinced that the history of oil painting in China should be moved back by about 100 years," Kuang says.

This significant chapter remains largely absent from Chinese textbooks, partly because most physical evidence was sold overseas, leaving few examples in China, according to Kuang.

Furthermore, Kuang says Chinese artists of the time, viewing China as the "Celestial Empire", often considered Western-style realism a "minor trick", and many felt too embarrassed to sign their names, leaving a generation of master painters anonymous.

Kuang later discovered clues in Crossman's The Decorative Arts of The China Trade about an image of Wu Guoying exhibited at the Boston Athenaeum in 1851.

The book places that black-and-white image alongside a portrait of Lin Zexu (1785-1850), a senior official of the Qing Dynasty, who ordered the historic destruction of opium in Guangzhou in 1839.

But, Kuang says, the Boston portrait was not the original. It was a later copy, made by Lam Qua (Kwan Kiu Cheong) and painted on a larger scale for exhibition.

Lam Qua, Kuang believes, was probably part of the same studio lineage — a family line or master-apprentice tradition — through which such images were reproduced.

"Workshop practice at that time was often family lineage or master-apprentice; each studio had its own subjects, and they generally weren't pirated," he says.

In addition, Kuang argues that Crossman mislabeled the subject as being Qiying (Chi Ying), even though the senior Qing Dynasty official bears little resemblance to him.

He says that such errors were common among foreigners who frequently mixed up Chinese names.